Community Commons - together-as-one

The community commons engages a diverse audience in exploration, discussion and engagement in the post-industrial rural landscape. Contributions from people in all disciplines are intended to foster connections among seemingly disparate methods and sensibilities. The introduction is a quote from aneight year art project by the Gianfranco Baruchello. His project was the development and operation of a farm in Italy, named Agricola Cornelia

- Westbrook Artists' Site (WAS) 2014

How to Imagine – A narrative on Art, Agriculture and Creativity (book by Gianfranco Baruchello and Henry Martin published 1984)

I wanted to start looking at things more clearly, and in doing so, I really began get interested in the soil, in the earth, in everything connected with them that was already going on around me. And I discovered that there was something passionate about it. There was something in the situation that had matured, and in myself had matured as I began to look at everything from this new point of view. And that was when I started a search for all the information I could find about, well, the idea of the grotto, the idea speleology, the kinds and nature and composition of terrain.

I got interested in old books about agriculture, and then in the myths and techniques of raising animals, and in the typical forms of social organization for agricultural work, in the ways they had failed and had had to be replaced. I started thinking in this new light about all the things we had been involved with before, the wells, the sewers, all sorts of hidden internal spaces, the insides of things, the back sides of things, the parasites that live beneath the surface of the earth, the snake that digs its burrow, the underground passageway, the grotto, the cricket mole, the rats, the birds, the cry you hear in the night, and all of this became part of an infinity of free-floating associations and allusions

For Lands Sake!

Roslea and Bob Johnson's Autumn tour

For Lands Sake! presented an updated vision statement. "Expand our stewardship community on behalf of our local natural habitats." and mission statement "Provide a welcoming group for people interested in stewardship. We will:

* Share experience, expertise and landscapes

* Educate and mentor our community

* Inspire action toward a living "land ethic"

* Leave land, water and air better for our efforts

For Lands Sake! presented an updated vision statement. "Expand our stewardship community on behalf of our local natural habitats." and mission statement "Provide a welcoming group for people interested in stewardship. We will:

* Share experience, expertise and landscapes

* Educate and mentor our community

* Inspire action toward a living "land ethic"

* Leave land, water and air better for our efforts

For Lands Sake! - Roslea and Bob Johnson Autumn Tour 9/27/15

For Lands Sake! - Roslea and Bob Johnson Autumn Tour 9/27/15

The old Peru Quarry is now in prairie restoration. Roslea has documented roughly 175 native species on the property. Some of these species are quite rare.... to very rare. The tours are always fun and the expertise that is shared is quite impressive and inspiring.

Iowa State University - Capstone Projects

Students from Iowa State

University toured Westbrook on a particularly cold day in February. The tour is part of their initial investigation

for their capstone projects. Students

from the forestry and wildlife ecology programs are working in teams to develop

strategies for enhancing the mission of WAS in supporting native ecology, sustainable agriculture and ethical

stewardship of the land. The tour was highlighted with sightings of a family about about a dozen deer on the move and a pair of bald eagles.

Ann Torke and Elizabeth Walden discuss Westbrook Artists’ Site (WAS) and the Fall 2014 Field Day in the context of contemporary art practices and environmentalism.

EW: Ann, you went to art school at a time when the experiments of the 1960s and 70s that broadened western conceptions of art practice were prevalent. The Field Day was an attempt at soil remediation and environmental action, but we also want to claim it as art. Can you help set out a context for this from your experience?

AT: I was fortunate to work with artists who were at the cutting edge of developments in the art world. An artist like Alan Kaprow was influential because he espoused the idea of “life as art.” This idea was really formative for my contemporaries and me because it meant that anything— all subjects and materials—could be art. And as such, it resituated the goals of art-making into a conceptual practice, the goal being to respond to and critique the world around us. Part and parcel of this was a radical departure from traditional understanding of sculpture. Minimalism, the movement that rose up in the 60’s in opposition to Abstract Expressionism, moved away from the expression of interiority and posited that space and site were new approaches to sculpture, rather than discipline being primarily a response to form. I recall thinking the word “context” was the emblem for this shift; it meant that you foregrounded place as integral to the meaning of work. We had a term for sculpture of the past, which was “plop art,” a derisive response to a bunch of hermetic objects that paid absolutely no attention to where they were put. Add to this the nascent environmental movement, the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency and ground breaking studies like Rachel Carson’s “The Silent Spring” and it is no surprise that artists wanted to move out of the gallery and respond to issues of import. Alongside performance, conceptual art, video art and installation, Environmental Art got its start in the 70’s and opened up a whole new way to think about art.

EW: I've been thinking about Kaprow as well as John Cage and Gianfranco Baruchello in this regard. Kaprow talks about the importance of producing art on the knife's edge between art and non-art, neither simply another object to collect nor habituated and invisible. Cage in 4'33 performs the absence of music so that the audience will attend to what they typically filter out, the ambient sounds of life. Baruchello, as an artist, farms in a wholly conventional way at Agricola Cornelia as a way to get people to "look at something that no one bothers to look at anymore." All of them are redeeming a world that has become disenchanted, divested of its ability to create a sense of wonder and appreciation. This gesture is critical at a time in which species extinction is rampant and the land is despoiled. At WAS we want to remediate the land, but we believe the way to do this is to make it present again in just this way. We want sustainability, bio-diversity, healthy soil, of course, but more than that we want to make the rich web of life of which we are a part visible.

What ideas were sparked for you specifically at the WAS Field Day?

AT: I recall thinking Cage was someone I wanted to emulate when I learned he spent his later years as a mycologist! Even in my 20's, I respected this shift. I knew Duchamp was similar in that he eschewed art in favor of chess (although I suppose you could argue this was a performance piece), but Cage's response was much more optimistic and shifted the frame away from human interaction toward a reverence for the earth.

I think contemporary artists whose work is relational, working with communities to affect and change dynamics are most interesting. Andrea Zittel, Mark Dion, Mel Chin, Natalie Jerimijenko, Agnes Denes and Fritz Haeg are examples of artists who make art that engenders a dialogue about landscape and our relation to it. And rather than offering ideas or suggestions for change, the work itself often posits solutions. For me as an artist, especially as I get older, I've become less interested in the "art world" per se & and more interested in finding ways to actually change something. Add to this the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of contemporary practice and it becomes clear that we all benefit from making alliances outside our respective disciplines. I want to dialogue with farmers, ecologists, economists, feminists and critical theorists to fully understand what's at stake.

What came to mind at the burn? Well again it seems there are some huge problems before us: climate change, big Agro's dependence on pesticides and mono-cultural approaches to farming. Not to mention the incredible disenfranchisement that has occurred in our relation to food. The consequence of these practices have had disastrous effects on health and sustainability of resources. It is a relief to me that many "answers" are already known, long forgotten practices we rejected in the name of progress. It isn't a romantic back-to-the-land fantasy, but rather a realignment of assumptions and goals. But to truly know, you have to actually test it. Ideas are not enough. Action is a necessary component. So I was happy to see such a broad range of participants. It is important to gain a sense that there is a community of people who want to solve these issues.

EW: I’m glad you invoke relational aesthetics. An important part of what we intended with the Field Day was to help create community around attention to environmental health. As industrial farms get bigger and small rural towns lose their young to the cities, the sense that the land is a common resource or the locus of community is endangered. We know that deep change only happens when people come together around a common goal. We want to embed environmental action within an aesthetic practice that revalues community, the commons, and our place in nature. It is the place of art to help us envision alternatives to the present.

As powerful as the Land Art of the 1970s was for shifting our ideas of art and making us attend to the landscape, it was still often a solitary and monumental artistic gesture. The contemporary artists you mention, some of Mel Chin’s work, Mark Dion’s etc, goes further by making the artist a partner with land, working with its natural processes. At WAS we work to de-center the human and its interests from our activities. The Field Day came about after a year of researching some of the plant species on the land, in particular the fascinating history of a common invasive species of grass, Bromus Inermis. Our guiding questions were What forms of life do we encounter here? What are their stories? And above all, what does the land want?

AT: I’m struck most by your intention of de-centering the artist. Exactly! So radically different than the mainstream art world that promotes the opposite and how tiresome too. Who cares about the cult of personality when climate change compels us to take responsibility for the human-based problems we’ve created? While I must function in a kind of state of denial of these issues in order to “carry-on” in every day life, there is no escape. At the end of the day, these questions, issues and problems are our new imperative, the most crucial issues facing us. And if I am to really pay attention, then it is my responsibility to strive to do something positive and tangible in an attempt to shift our collective consciousness toward responsible stewardship of the earth. Here I am sitting home for the fifth snow day this semester, watching record amounts of snow accumulate in the northeast; I can’t help but see my position affirmed all around me. At what point do we respond? At what point do we take responsibility? At what point do we affirm that humans are a mere blip on the timeline of the universe, and that if we are to do anything meaningful, it is to take responsibility for our impact?

As powerful as the Land Art of the 1970s was for shifting our ideas of art and making us attend to the landscape, it was still often a solitary and monumental artistic gesture. The contemporary artists you mention, some of Mel Chin’s work, Mark Dion’s etc, goes further by making the artist a partner with land, working with its natural processes. At WAS we work to de-center the human and its interests from our activities. The Field Day came about after a year of researching some of the plant species on the land, in particular the fascinating history of a common invasive species of grass, Bromus Inermis. Our guiding questions were What forms of life do we encounter here? What are their stories? And above all, what does the land want?

AT: I’m struck most by your intention of de-centering the artist. Exactly! So radically different than the mainstream art world that promotes the opposite and how tiresome too. Who cares about the cult of personality when climate change compels us to take responsibility for the human-based problems we’ve created? While I must function in a kind of state of denial of these issues in order to “carry-on” in every day life, there is no escape. At the end of the day, these questions, issues and problems are our new imperative, the most crucial issues facing us. And if I am to really pay attention, then it is my responsibility to strive to do something positive and tangible in an attempt to shift our collective consciousness toward responsible stewardship of the earth. Here I am sitting home for the fifth snow day this semester, watching record amounts of snow accumulate in the northeast; I can’t help but see my position affirmed all around me. At what point do we respond? At what point do we take responsibility? At what point do we affirm that humans are a mere blip on the timeline of the universe, and that if we are to do anything meaningful, it is to take responsibility for our impact?

Mikesch Muecke

Hypnerotomachia Pyrotechnica

In the morning of 11 October 2014 I pointed the nose of my car south toward Madison County, leaving Ames around 8:00 a.m. to participate as an academic observer (my own definition) in the Field Day organized by my colleague Kevin Lair who had invited the public and a few of his friends from the Iowa Farm Bureau to assist in a prairie burn on his property.

When I arrived on that crisp Saturday morning just after 9:00 a.m. the burn leader was going over the safety procedures for the planned burn next to the Westbrook Artists’ Site barn. We were standing as a group of perhaps twenty individuals around the small core of professionals tasked with setting fire to a meadow southwest of the Holliwell Covered Bridge. There was a dampness to the chilly air, the rising sun had not yet burned off the dew that had built up overnight, and the temperature was only slowly rising. The mood appeared to be expectant of something new and unusual, at least for most of us, and certainly for those who had only played with fire as a child or who recently used matches to light candles.

Handling the metal kerosene torches that seem to have tesseracted straight from the 1800s into the 21st century, it became clear that this would not be a conventional Saturday. The weight of the instrument, it’s potential for destruction weighed heavy on those who tried soon to set fire to small sections of the prairie, only to see the flames die down quickly in the still wet morning air.

Fire is a crucial part of nature’s regeneration process. When I lived in Florida, the state with the highest frequency of lighting strikes, my partner and I would visit state parks where year after year forest officials would set fire to the underbrush to help along the process of regeneration, but only if nature didn’t intervene earlier by setting fire herself with lightning. A few weeks after a burn we would witness the restorative power of plants as the new growth emerged out of the scorched blackness of the cleared flora. It always seemed like a miracle that the trees survived the fire but given the speed with which the flames move through the brush the cooking of small plants did not affect their arboreal cousins in any major way, except for their crisped bark.

The ecological benefit of this planned burn at WAS is beyond doubt. That the burn didn’t happen had nothing to do with the expertise of the burn team, and everything to do with the vagaries of the Middle River which flooded the field earlier in the year, and left a thin layer of inflammable mud on the first four or so inches of the plants that we tried to set on fire. That resistant mud was enough to extinguish the licking kerosene flames again and again, until the operation was frustratingly called to an end by the burn leader. However, the learning about the importance of controlled burns and their impact on flora and fauna still happened, and from my perspective the pedagogical dimension was certainly more important than a fire that continues to run out of fuel.

Furthermore, taking part in a potential pyrotechnic event in the bread basket of the country on a cold and sunny October morning has also a dreamlike dimension, not unlike that the protagonist experienced in Colonna’s 1499 text Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, that strange romance story about Poliphilo and his love interest Polia. On this morning in that field next to the Westbrook Artist’s Site the desire to destroy for a reason, to decimate in an orderly fashion, to set fire to nature in a controlled manner—as if fire outside is something that can be controlled—appeared to me in retrospect as a rational beard for the emotional dimension that defines setting fire to something that is larger than us. It wasn’t the craziness of Nero that drove those present but I would think that the secret wish for setting something on fire goes hand in hand with the expressed desire to preserve our environment. There is a time for destruction and decay, and there is a time for rebirth and growth. The destruction didn’t happen that morning but it will at some point in the future, whether we plan it or not, and soon thereafter small plants will poke their bright green leaves through the charred earth in defiance.

Mikesch Muecke, Ph.D., Ames, 22 January 2015

Gregg Pattison, Private Lands Biologist, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, 10/2014

Gregg Pattison addressing the group during the field day and demonstration burn 10/11/14 at WAS

Gregg Pattison addressing the group during the field day and demonstration burn 10/11/14 at WAS

Community leaders and landowners are vital partners in conservation. Landowners and community volunteers have the ability to manage their property in a sustainable manner that supports diverse native plant communities that contribute to healthy ecosystems for widlife, improved water and air quality while maintaining a working landscape that provides for their families. In Iowa, only 2% of the land is in public ownership. Private landowners must be willing to complete conservation practices on their properties in order for any conservation efforts to succeed. Educational and outreach events such as the Prescribed Burn Workshop at the Westbrook Artists Site are critical in helping spread the knowledge and understanding of how diverse ecosystems improve many aspects of human lives, including water quality, pollinator habitat, aesthetic value, open spaces and recreational opportunities. These workshops also give hands on experience for the participants in the process of restoration and maintenance of any conservation areas they establish. People go away from these workshops with knowledge, enthusiasm and drive to complete conservation practices on their properties. In particular in this Prescribed Burn Workshop, participants learned how fire interacts with grassland (prairie) habitats to increase plant diversity, improve soil structure to absorb more water, and how fire creates a mosaic of diverse habitat structure within an area that contributes to diverse wildlife use of the area.

Community leaders take the information from these workshops and complete work on their properties and share their enthusiasm with their neighbors who then take up the effort to improve conservation on their property. Eventually, good land management practices that include conservation of resources, become the natural way of managing the land. The Southern Iowa Oak Savanna Alliance (SIOSA) and the Madison County Landowner Conservation Group - For Lands Sake - are great examples of how community leaders have stepped up to share information and promote healthy ecosystems and sustainable land use practices. Each acre of habitat restored or protected helps achieve the goal of a sustainable and healthy landscape for future generations.

Community leaders take the information from these workshops and complete work on their properties and share their enthusiasm with their neighbors who then take up the effort to improve conservation on their property. Eventually, good land management practices that include conservation of resources, become the natural way of managing the land. The Southern Iowa Oak Savanna Alliance (SIOSA) and the Madison County Landowner Conservation Group - For Lands Sake - are great examples of how community leaders have stepped up to share information and promote healthy ecosystems and sustainable land use practices. Each acre of habitat restored or protected helps achieve the goal of a sustainable and healthy landscape for future generations.

Allendan - (For Lands Sake!)

contributor, K. Lair

Allendan Seed Company in Madison County was converted over thirty years ago from a family production swine operation into a seed stock producer for native plants. A tour of Allendan in summery of 2014 was organized by a local landowners initiative created to shared knowledge, skills and resources for rehabilitating prairies, savannas, and woodlands. Allendan was gracious with their time and information regarding their operation and mission to create high quality native seed stock. In prior visits, to Allendan they have always been more than friendly and helpful.

The ideal conditions are when the native plants at a location are those that have developed continuously since pre-settlement to protect genetic diversity that is particular suited to its ecology. Prairie remnants that have remained relatively undisturbed and intact cannot be replaced. A story was told at Allendan regarding a landowner who recently inherited control of this land from his father. Part of this land had been one of the few remnants that provided this valued native seed for maintaining the localized genetic character in the area. The son, in what now seems an act of defiance, plowed up the land stating that the remnant had been his fathers (and not his son’s.)

Of course, there is nothing in place to provide protection for native ecology preservation in this situation. The notion of unreplaceable pieces of our ecology that may have been around for eons being sacrificed in the pursuit of personal gain is nothing new. The stories are so familiar that they often fail to surprise us let alone motivate us to take action. This variation on the theme has the twist that perhaps the motivation has even more personal and merely a way to separate the present from the past within a family did strike a chord and particularly frustrating and counter-productive even for landowner who plowed the remnant. For perhaps the way to preserve small scale, independent farming as a way of life is through new practices and an ecologically attuned approach. However, it was clear that for some there is no persuasive argument to be made and we have lost a particular piece of environmental history in a move that is emblematically of why we need to reclaim a far greater sense that we are in this together.

The son’s attitude that the land was merely “his father’s” and now it is his land, rather than part of something far more extensive reflects a common understanding of many people. However, those in local initiative of landowners now called, “For Lands Sake!,” possess the sense of the land as something more. The organization arose from an incidental conversation when then tapped into the emerging interests from farmers and other stakeholders. The individual’s interests are commonly expressed through experiences and through a tacit formation of curiosity, awareness and desire. This is formation is fundamentally creative as it seeks more to realize greater potential in the land and our relationship with it.

The ideal conditions are when the native plants at a location are those that have developed continuously since pre-settlement to protect genetic diversity that is particular suited to its ecology. Prairie remnants that have remained relatively undisturbed and intact cannot be replaced. A story was told at Allendan regarding a landowner who recently inherited control of this land from his father. Part of this land had been one of the few remnants that provided this valued native seed for maintaining the localized genetic character in the area. The son, in what now seems an act of defiance, plowed up the land stating that the remnant had been his fathers (and not his son’s.)

Of course, there is nothing in place to provide protection for native ecology preservation in this situation. The notion of unreplaceable pieces of our ecology that may have been around for eons being sacrificed in the pursuit of personal gain is nothing new. The stories are so familiar that they often fail to surprise us let alone motivate us to take action. This variation on the theme has the twist that perhaps the motivation has even more personal and merely a way to separate the present from the past within a family did strike a chord and particularly frustrating and counter-productive even for landowner who plowed the remnant. For perhaps the way to preserve small scale, independent farming as a way of life is through new practices and an ecologically attuned approach. However, it was clear that for some there is no persuasive argument to be made and we have lost a particular piece of environmental history in a move that is emblematically of why we need to reclaim a far greater sense that we are in this together.

The son’s attitude that the land was merely “his father’s” and now it is his land, rather than part of something far more extensive reflects a common understanding of many people. However, those in local initiative of landowners now called, “For Lands Sake!,” possess the sense of the land as something more. The organization arose from an incidental conversation when then tapped into the emerging interests from farmers and other stakeholders. The individual’s interests are commonly expressed through experiences and through a tacit formation of curiosity, awareness and desire. This is formation is fundamentally creative as it seeks more to realize greater potential in the land and our relationship with it.

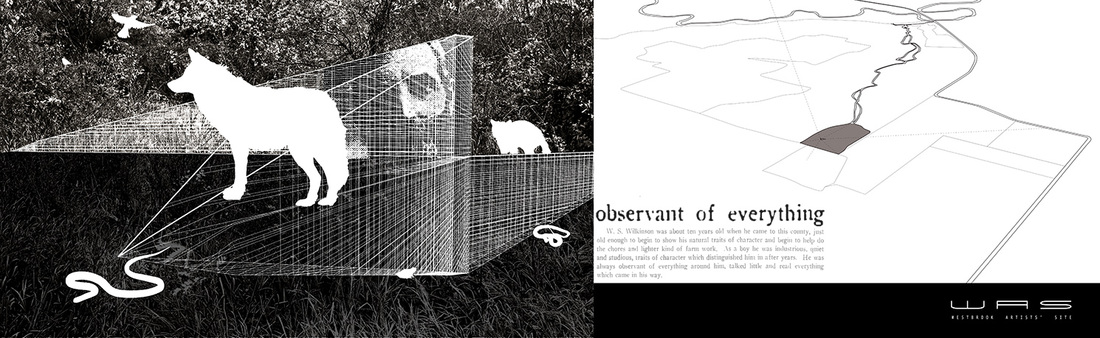

Project sketch for WAS - K. Lair (2014)

John Wilkinson was born in Ireland in 1803. He moved from near Hopkinsville, KY to Pike, IL in 1824. The family moved to south of Des Moines in 1846 and then in the spring of 1847 they were one of the first settlers to Madison County, IA. They built a home on a claim this is now part of the Westbrook Artists’ Site (WAS). He lived there until his death in 1869. One of their ten children was W. S. Wilkinson. W.S. Wilkinson was perhaps the most significant contributor to the development of the County Historical Society. From the History of Madison County, 1915 vo1.2 “No other member of the historical society did as much as he to keep the society alive and store its rooms with interesting relics and valuable records.” However, the original records of W.S. Wilkinson and what items he collected, I have not been able to find if they still exist

I have been seeking to understand the environmental history of the land at Westbrook Artists’ Site (WAS) in order to inform our efforts for rehabilitation of native ecology. This has evolved into a micro-history of the site starting with the original European settlement of the land. The perspective driving early settlement was to “improve” the land and transform the prairie into farmsteads. The project in development (see work in progress image “observant of everything”) is a reflection of the role of history and ecology in the post-industrial rural condition. Through this project the site of the original Wilkinson homestead is intended to support diversity and native species lost to settlement. In addition, the demarcation of the original site will provide not only an aid in the preservation of the history of the site but will also become a location for collection of new information about the site. The conceptual sketch is based on locating the homestead in relation to other area landmarks. This is to indicate that the project will be developed not to recreate the artifact of the homestead. The image used in the collage is very close to the actual site of the homestead. The site map is based on images from the 1930’s. The road to the original homestead is still faintly etched into the site today. When the first settlers arrived, there were no established roads so the Wilkinson homestead was far from where the public roads were eventually established.

One of the other early settlers at the Westbrook Artists’ Site was a prominent landowner in Kentucky, and his son was a minister/farmer and vocal abolitionist. In 1860, as the issue of slavery heated up in Kentucky, they and their family moved to homestead at WAS. They are both buried nearby. His descendants are prominent in the local community today and active in prairie rehabilitation and habitat.

I have been seeking to understand the environmental history of the land at Westbrook Artists’ Site (WAS) in order to inform our efforts for rehabilitation of native ecology. This has evolved into a micro-history of the site starting with the original European settlement of the land. The perspective driving early settlement was to “improve” the land and transform the prairie into farmsteads. The project in development (see work in progress image “observant of everything”) is a reflection of the role of history and ecology in the post-industrial rural condition. Through this project the site of the original Wilkinson homestead is intended to support diversity and native species lost to settlement. In addition, the demarcation of the original site will provide not only an aid in the preservation of the history of the site but will also become a location for collection of new information about the site. The conceptual sketch is based on locating the homestead in relation to other area landmarks. This is to indicate that the project will be developed not to recreate the artifact of the homestead. The image used in the collage is very close to the actual site of the homestead. The site map is based on images from the 1930’s. The road to the original homestead is still faintly etched into the site today. When the first settlers arrived, there were no established roads so the Wilkinson homestead was far from where the public roads were eventually established.

One of the other early settlers at the Westbrook Artists’ Site was a prominent landowner in Kentucky, and his son was a minister/farmer and vocal abolitionist. In 1860, as the issue of slavery heated up in Kentucky, they and their family moved to homestead at WAS. They are both buried nearby. His descendants are prominent in the local community today and active in prairie rehabilitation and habitat.

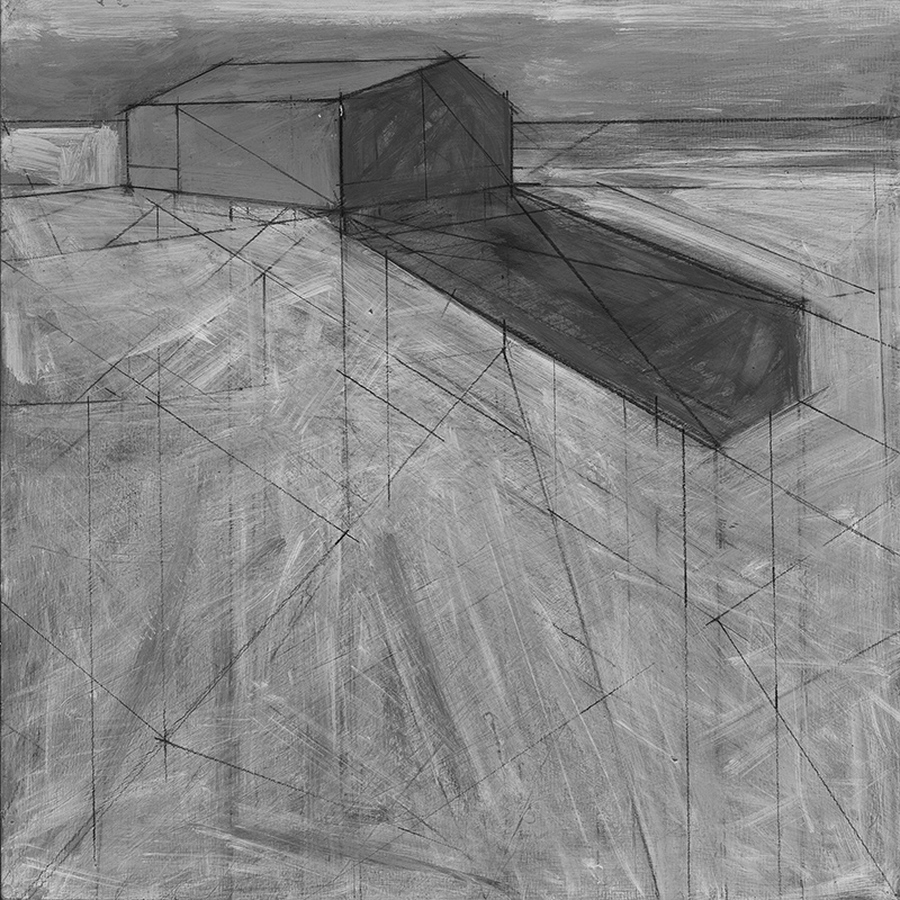

A sketch study that took an unexpected trajectory .. probably not very helpful for the project in mind but posting as a process piece., One of the key points of interest in the settler's history of Madison County is the need for each setter to create firebreaks against prairie fires around their "improved" land. I am exploring how to bring the tracings on the land and the history into this new project. I am interested in using steel cables and thin welded steel rods for semi-temporary installations - K. Lair