The Rural Post-Industrial as Site of Aesthetic Engagement and Transformation

Exploring the currents of the industrial (past and present) on the land. Fragments, histories, erosion, exploitation, tracings, absence. Additional work.

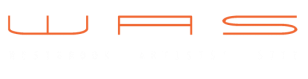

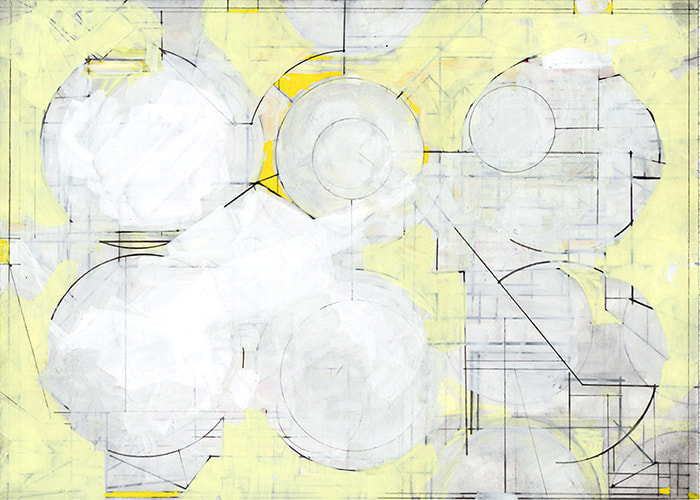

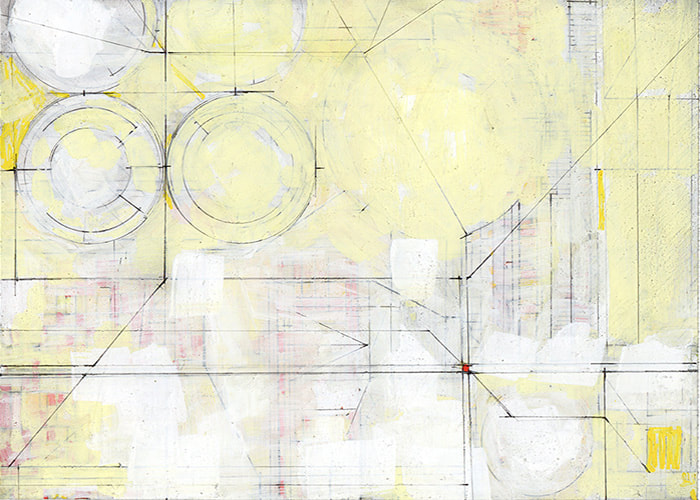

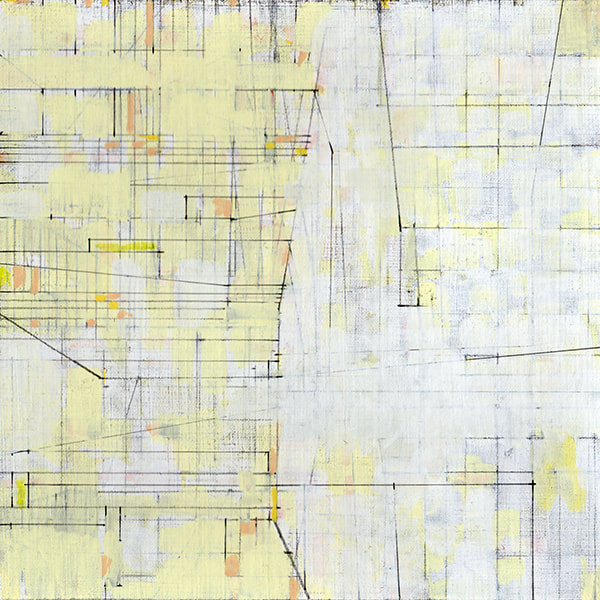

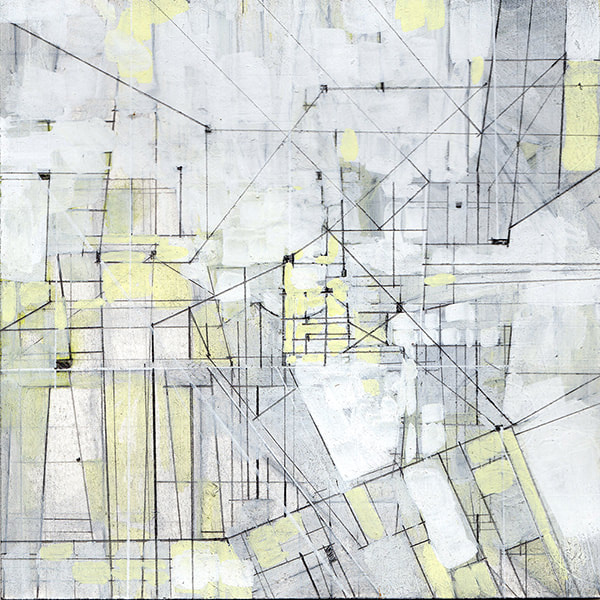

K. Lair. Graphite, mixed-media on paper 9" x 12". 2019

K. Lair. Graphite, mixed-media on paper 9" x 12". 2019

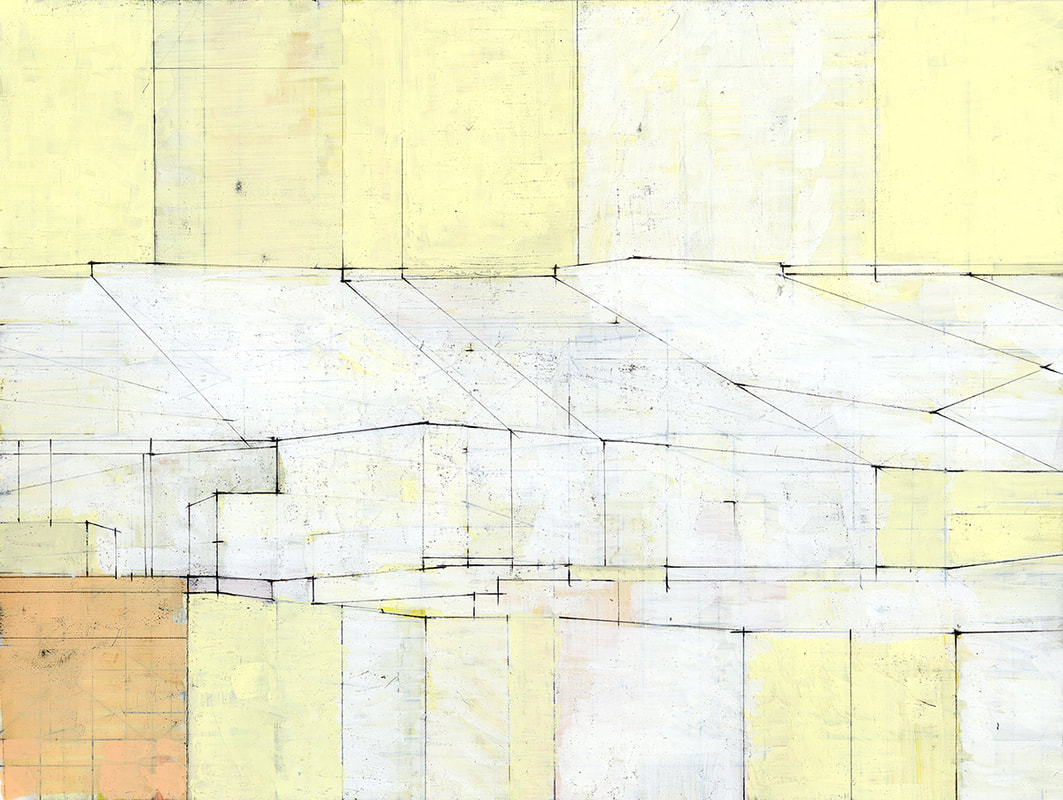

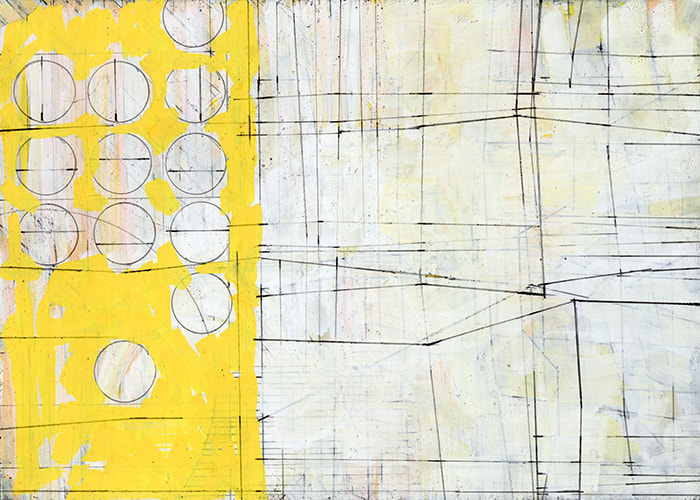

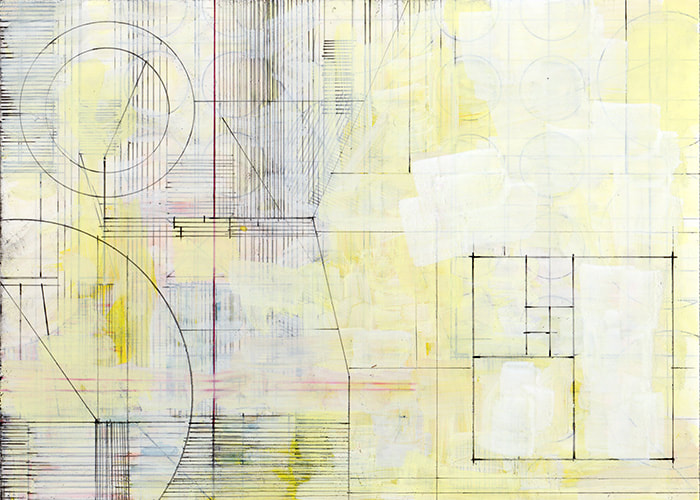

Graphite and acrylic on paper (group each 5" x 7") 2019

Graphite and acrylic on paper (group each 5" x 7") 2019

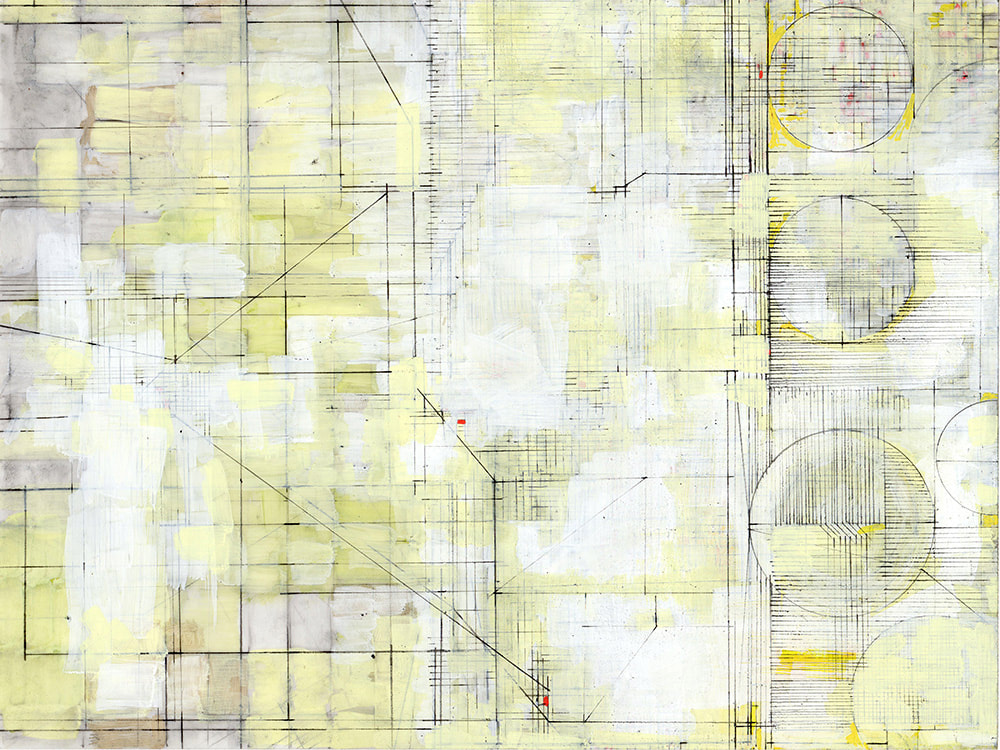

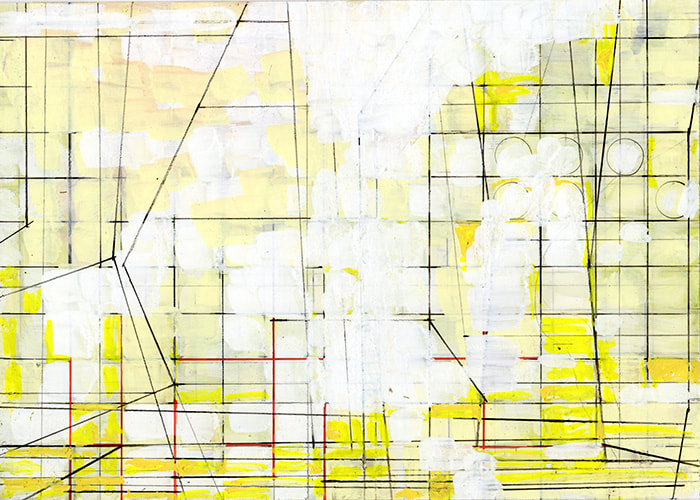

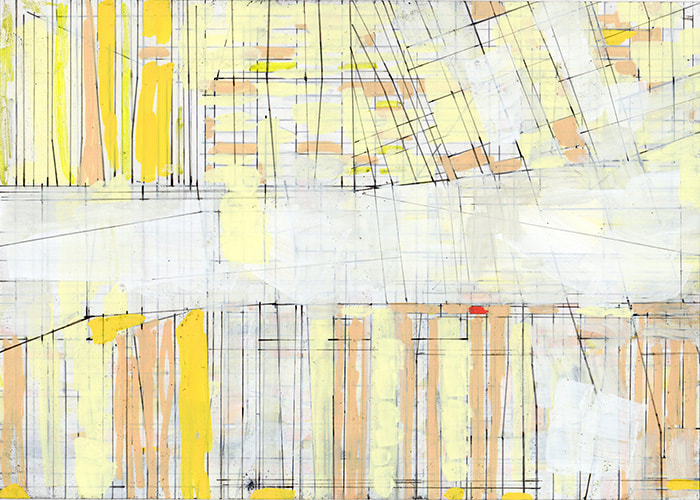

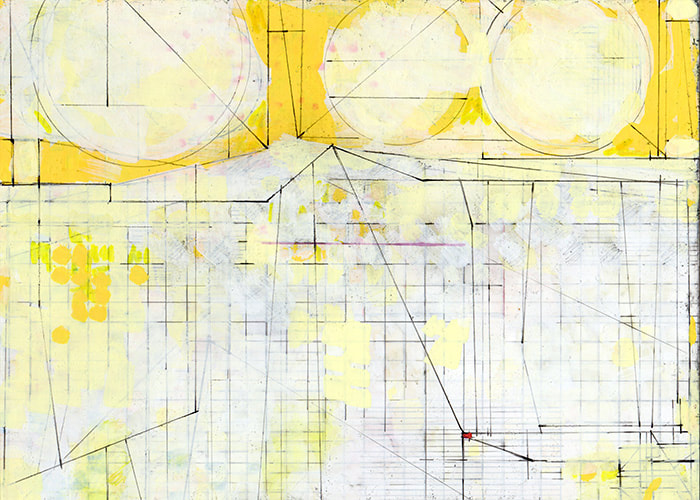

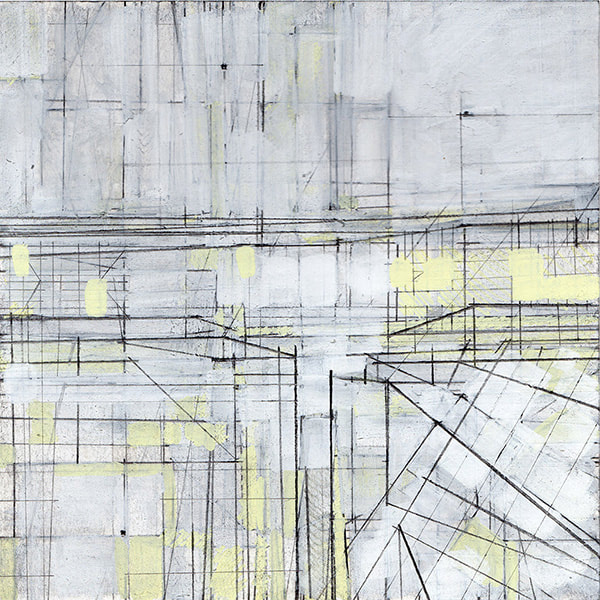

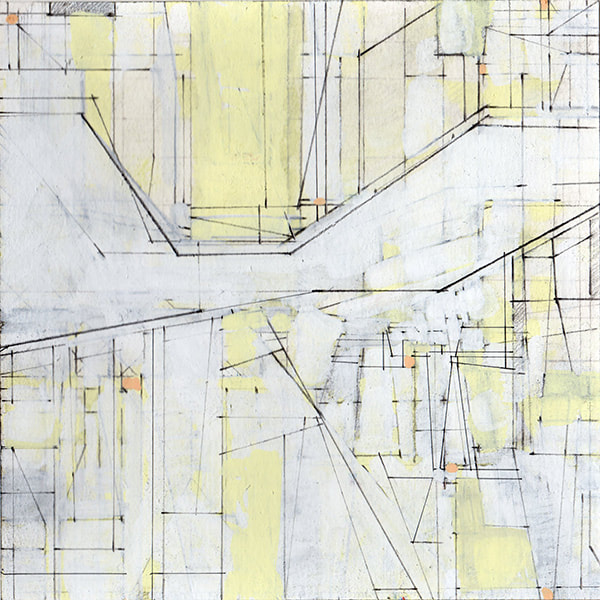

Graphite/acrylic on paper ( 6" x 6") 2019

Graphite/acrylic on paper (each 6" x 6") 2018-19

Westbrook Artists' Site

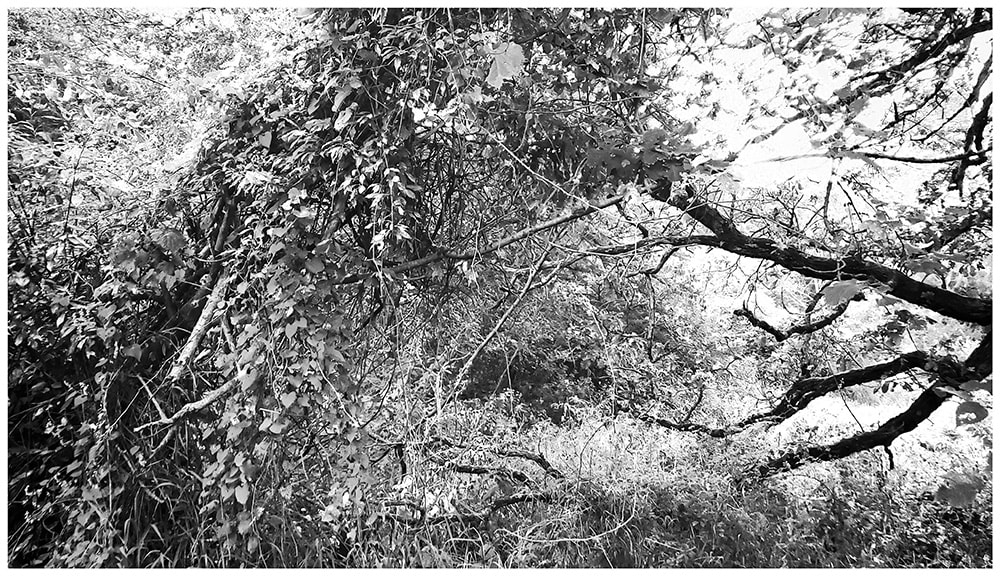

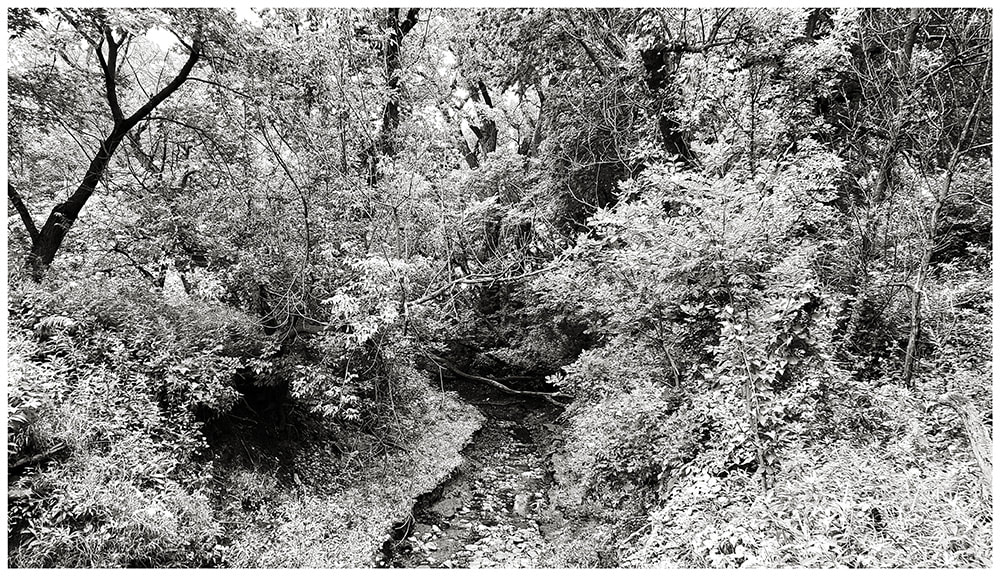

- K. Lair. Post-Industrial 045, 2020

K. Lair. Creek 0240, 2019.

K. Lair. Creek 0200. 2019

K. Lair. River Willows 020, 2019

K. Lair. Middle River bend 050, 2019

K. Lair, Wetland 0100, 03/19

K. Lair. Fencerow 0150., 02/2019

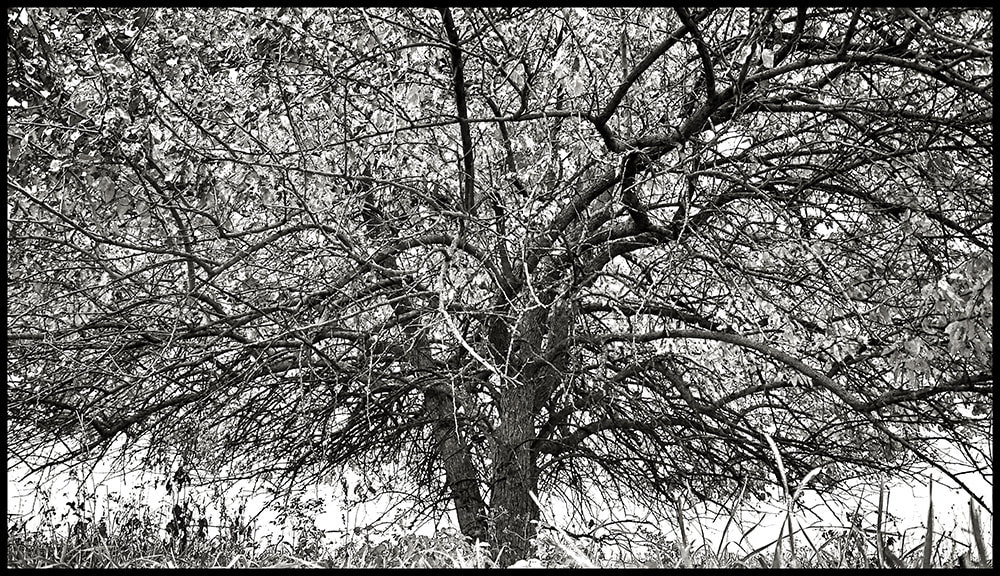

K. Lair, Wild apple in fence line, digital image, 2019

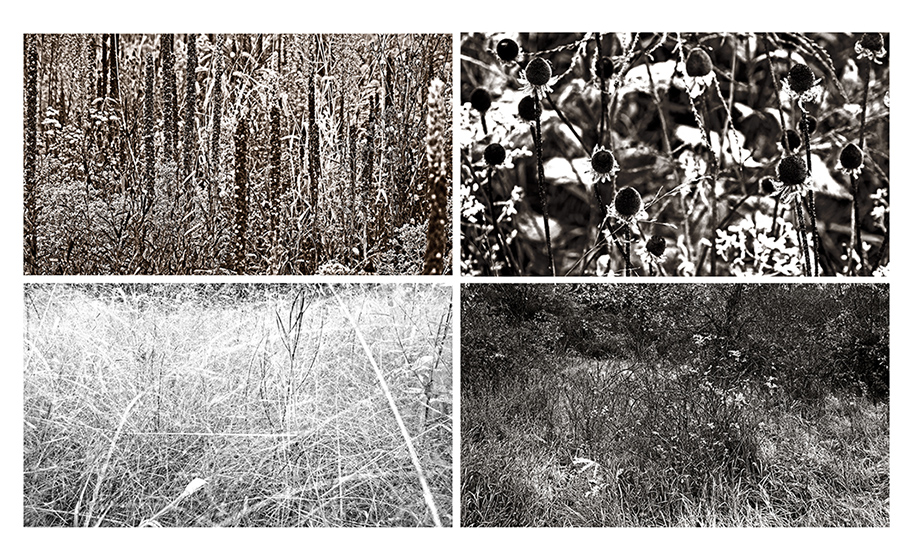

K.Lair. (bottom left, Cellar, bottom right Willow and tails at Northbrook II, top, Willow and tails at Northbrook I, 2019

K. Lair. Tree 050, 02/19

K. Lair. Island and bank, 2018

K.Lair. Middle River (sand and soil 05) and Creek 0100, 12/18.

K.Lair. Current (MR) (top left) and Field well A1 (top right) Plunge (bottom left) and Bridge HB010 (bottom right)., 2018

K. Lair. Framed locust pods, 2018

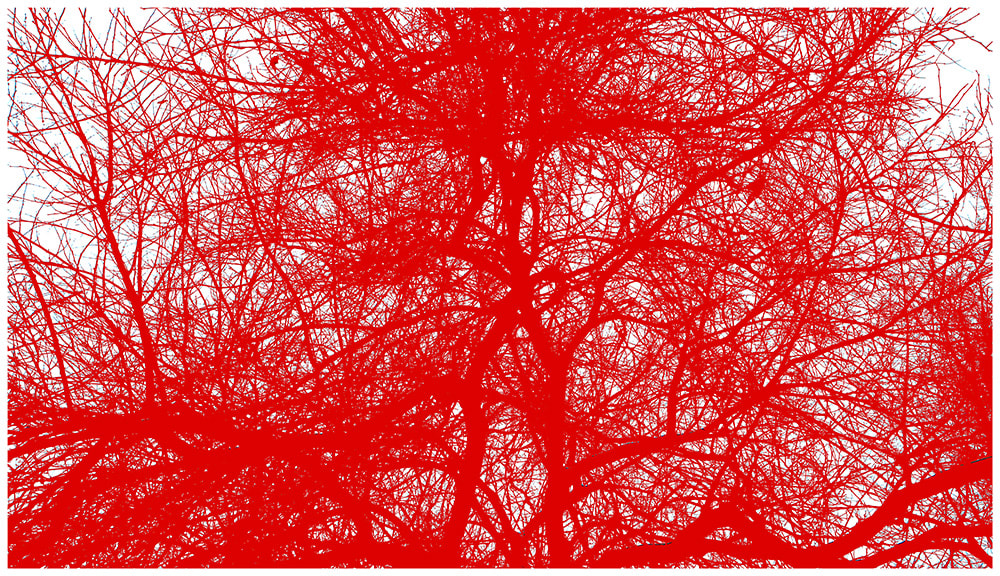

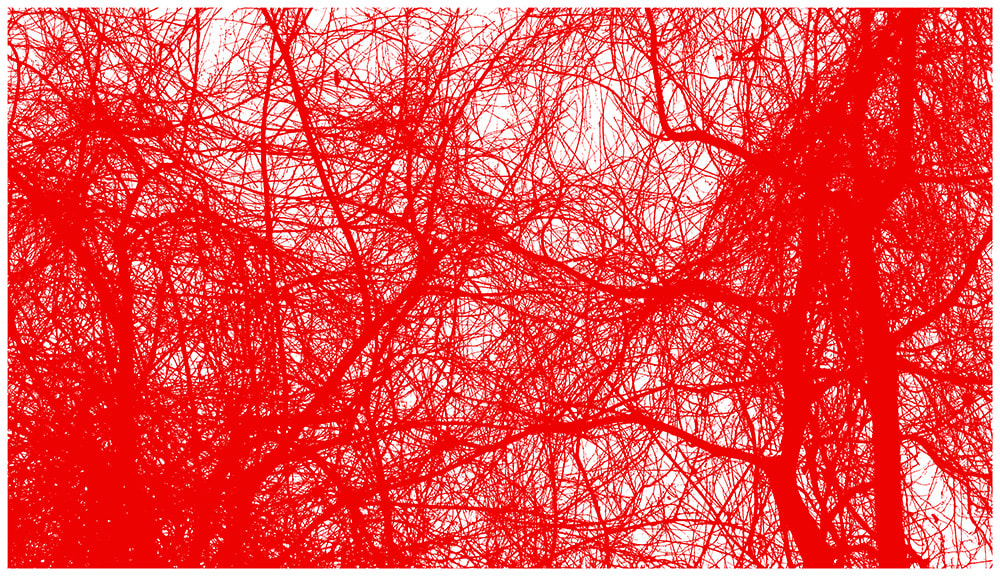

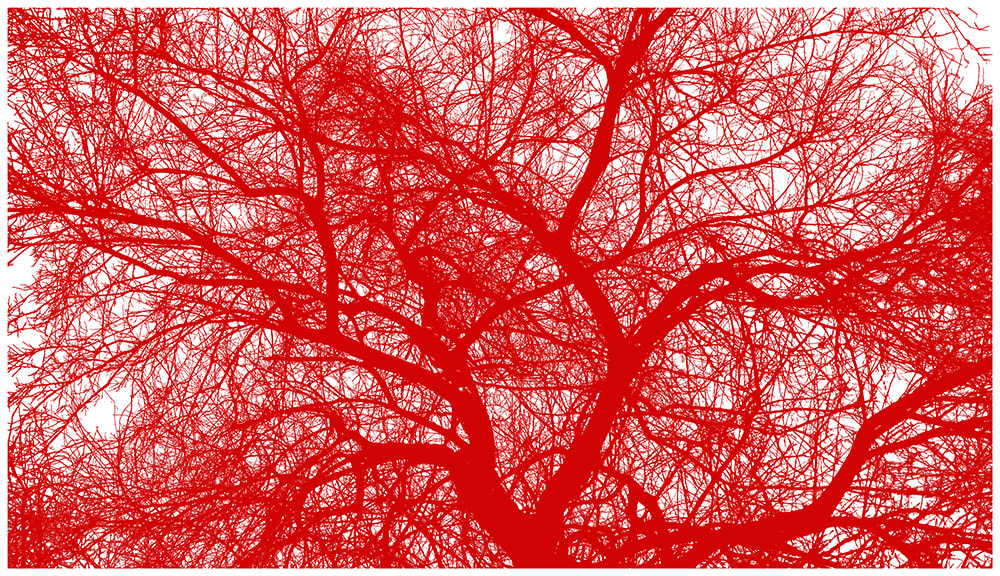

K.Lair top left (RED) top right (RED) 0400 0300 bottom right (RED) 0200 and bottom left (RED) 0100, 2019

K. Lair. 01/19

K. Lair. Central IA W19 _0100

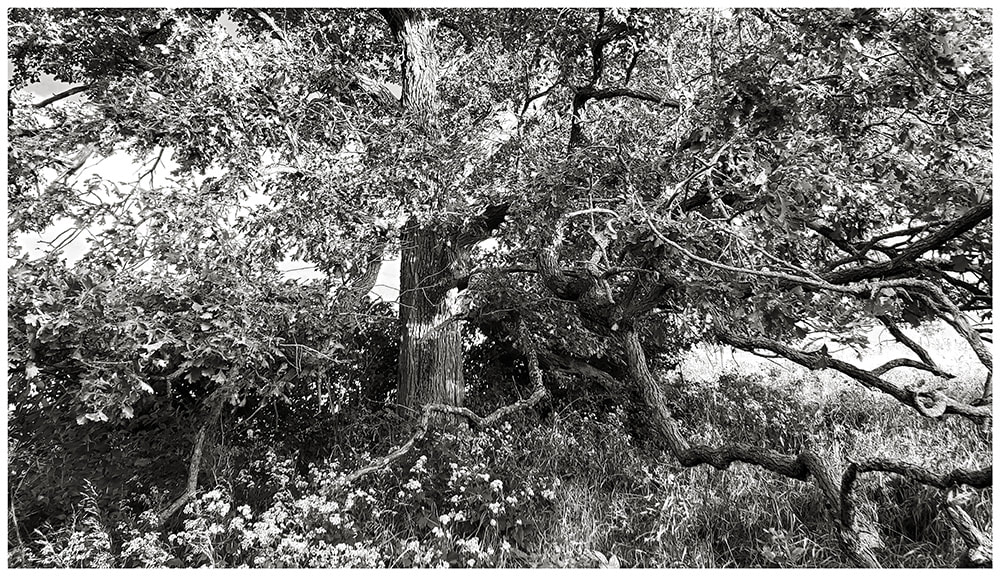

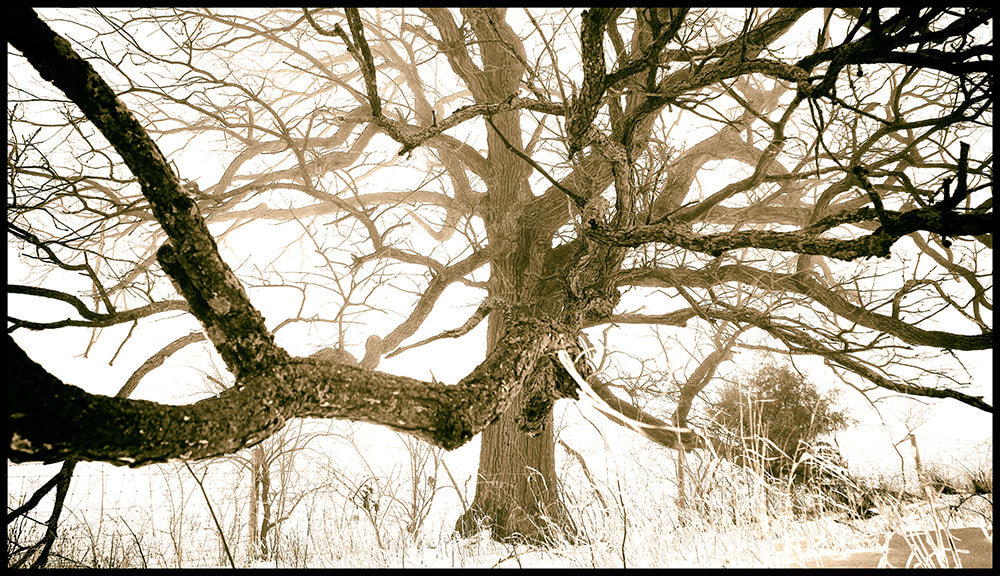

K. Lair. Wolf Tree (Bur Oak) 0150, 09/19 (left) Wolf Tree (Bur Oak) 0100, 02/19

A work in progress.

The Middle River. The disruption to the land by production agriculture creates a numerous issues for the conditions of our rivers. Flooding left a massive river dam full of large snags that has persisted for several years and seems to be a permanent feature of the bank along WAS.

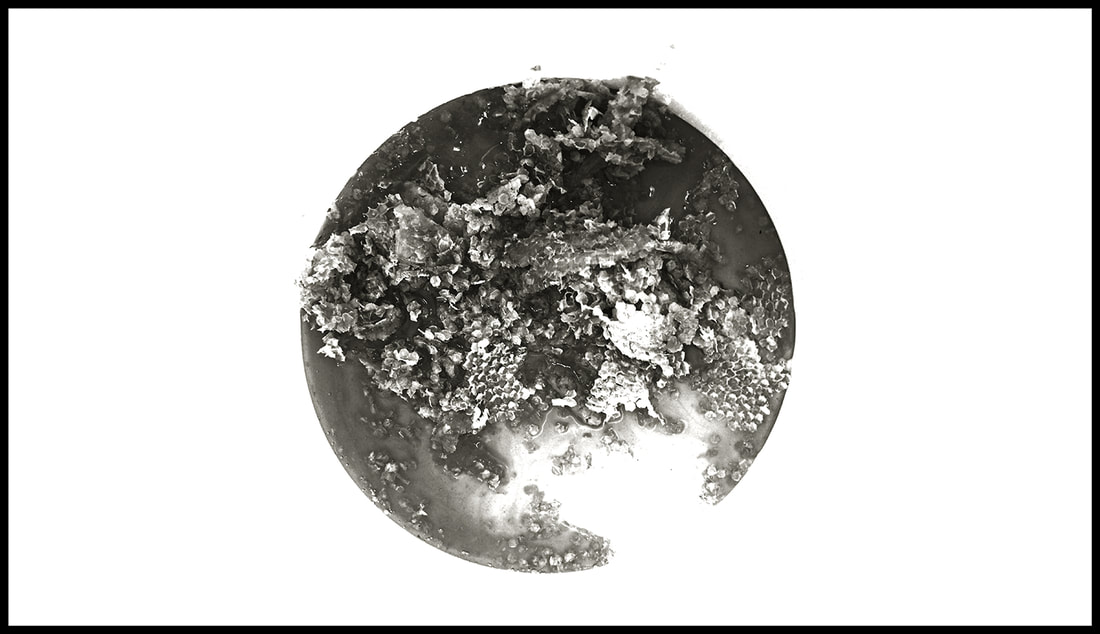

WAS 11/17 - "Hedge Apple" or fruit of Osage Orange.

Osage Orange Tree (11/17)

This Osage Orange stands alone. It is isolated on a back portion of WAS that we rarely visited for years and thus in 2012 it really seemed to be a discovery. It is now integrated into the trails at WAS and we make daily treks to see it. The Osage Orange is interesting tree with a significant history in the rural landscape. It was used as live fencing by settlers and its fruit as an insect repellent.

This Osage Orange has a vivid character and sense of connection for us. It is a non-native but seems well suited for this place.

This Osage Orange has a vivid character and sense of connection for us. It is a non-native but seems well suited for this place.

There are several water features at WAS including a pond on the main property. The expansion of the American Bullfrog population at WAS was one of the initial drivers for developing a new mission. We have been considering how to address the bullfrog but also the entire ecology of the pond. In the summer of 2014, we added a "Habitat Log" to support amphibian populations such as turtles. We hope to establish a diverse wildlife habitat at the pond in the coming years.

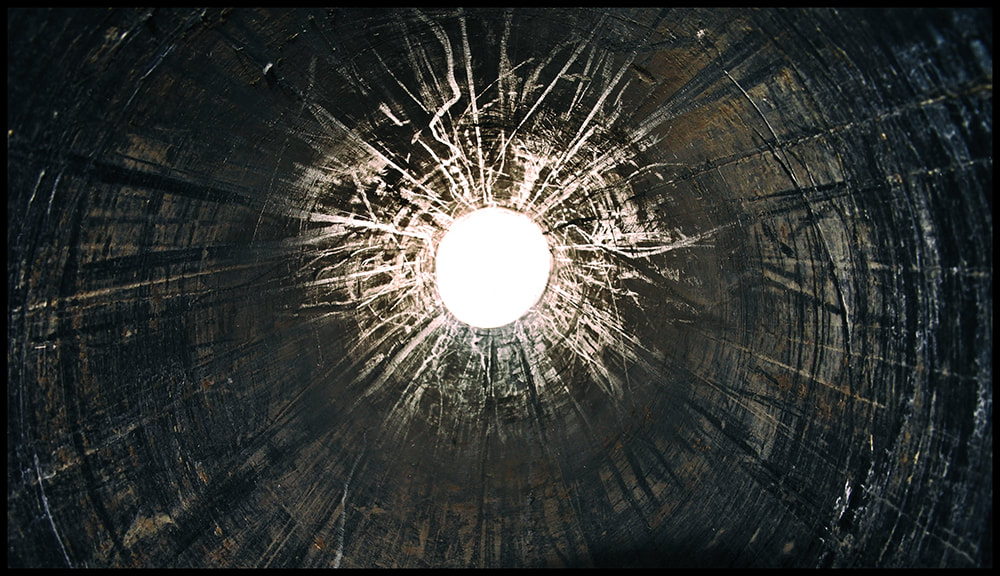

Bútugaiŋe - Quercus macrocarpa

Bútugaiŋe - Quercus macrocarpa is a series of work based on the highly endangered Oak Savanna. Only .02 percent of Midwest Oak Savanna remains today. A recent storm with high winds damaged several trees at WAS and completely uprooted one Oak. The recent work with the trees focuses on appreciation of their individuality and finding meaning in the simple texture and quality of each tree. The Bur Oak exhibits character and a unique print in its thick, coarse bark that tends to show the environmental effects and distress. A few trees that make it to maturity may live a few hundred years and provide a directly link to the pre-settlement times.

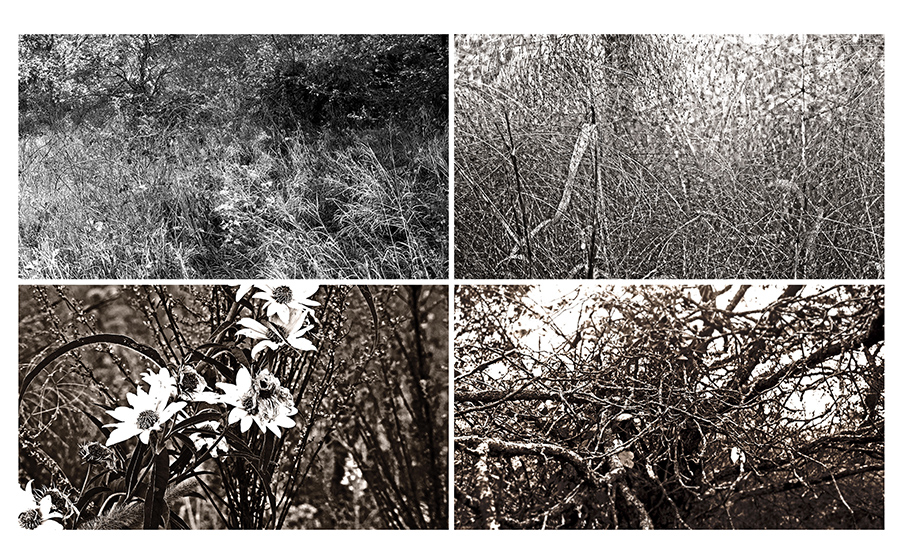

K. Lair, from series F14_A, digital image, 2014

K. Lair, from series F14_A, digital image, 2014

The Rural Post-Industrial Site as Site of Aesthetic Engagement and Transformation - The site for this inquiry is the landscape of the Midwest, which was defined by tallgrass prairie before its radical transformation by European settlers into a leading agricultural center during the middle of the 1800s[i]. Industrialization fostered production efficiency through scale and new technologies, reducing human labor and increasing output. In our current situation few people are needed to farm the land and farms are becoming fewer and larger. The notion of “peak farmland,” a time when land can be removed from agricultural production is no longer tenable because it was based on industrial farming methods that are unsustainable. Hence, the very notion of a “post-industrial” rural condition may seem to be mired in contradictions. But I am using the term to acknowledge the significance of pre-industrial knowledge and practices and the values of cultural and material vibrancy and biodiversity. The post-industrial condition is defined by interdependencies, not the isolation of elements within discrete parts which is the model characteristic of industrial practices. The functional grids and boundaries overlaid across the Midwest invoke a sense of predictable regularity and aesthetics of human dominance over nature through “improvement” of the land. The establishment, transgression and transformation of boundaries on the land itself, between nature and culture, human and nonhuman and the role of human engagement, management and control of the environment are the dominant themes that emerged during our exploration of the post-industrial rural landscape. While terms such as conservation and restoration may imply we have the ability to undo the effects of industrial agriculture; in reality, it is a boundary we can no longer transgress. An exploration of the tension between control and that which escapes or eludes our control suggests how we may reconnect to hidden or lost dimensions of the post-industrial rural environment.

The images on this page come from various sub-series of work such as the Bútugaiŋe - Quercus macrocarpa. There are also images collected from the WAS site that are yet to be assembled into a series but may just have been part of the general inquiry. The idea of the post-industrial rural condition is an on-going exploration.

[i] Cornelia F. Mutel. The Emerald Horizon – The History of Nature in Iowa, (Iowa City, The University of Iowa Press 2008) pp. 14

Creative inquiry in art + design - Using art, history, design, architecture, ecology and agriculture in creative place-making

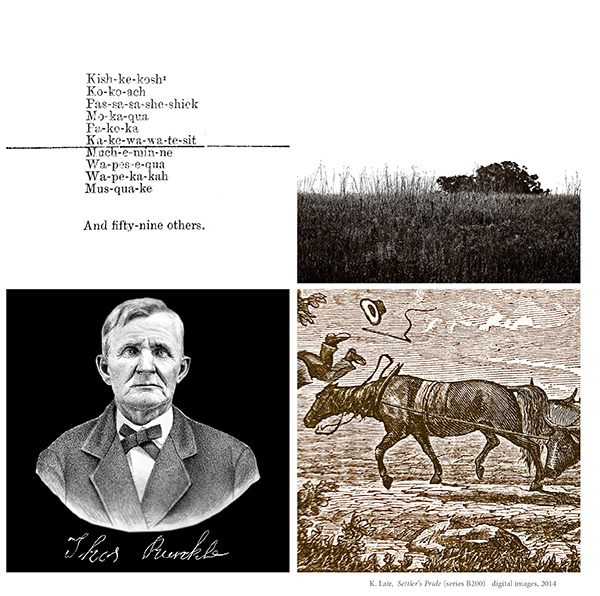

Carl Sauer wrote in 1955, “We present and recommend to the world a blueprint of what works well with us at the moment, heedless to that we may be destroying wise and durable native systems of living with the land. The modern industrial mood is insensitive to other ways and values. ” Since our arrival on the prairie, as Frieda Knobloch asserts, we have systematically tried to “conquer the wild and replace it with the tame or useful.” The belief that materials, landscapes, and inhabitants are essentially empty, passive things awaiting the vision, agency and industry of man to make them either into something or change them into something of value was prevalent in our early settlement and still prevails today. In this sense architecture and agriculture have a shared sensibility. The series of work “Settlers’ Pride” draws on historical perspectives to bring into context and question our acts of “improvement” to the land. It is an attempt to highlight the cultural frames that engender us to conclude that “progress” and our actions are inevitable or desirable.

Carl Sauer wrote in 1955, “We present and recommend to the world a blueprint of what works well with us at the moment, heedless to that we may be destroying wise and durable native systems of living with the land. The modern industrial mood is insensitive to other ways and values. ” Since our arrival on the prairie, as Frieda Knobloch asserts, we have systematically tried to “conquer the wild and replace it with the tame or useful.” The belief that materials, landscapes, and inhabitants are essentially empty, passive things awaiting the vision, agency and industry of man to make them either into something or change them into something of value was prevalent in our early settlement and still prevails today. In this sense architecture and agriculture have a shared sensibility. The series of work “Settlers’ Pride” draws on historical perspectives to bring into context and question our acts of “improvement” to the land. It is an attempt to highlight the cultural frames that engender us to conclude that “progress” and our actions are inevitable or desirable.

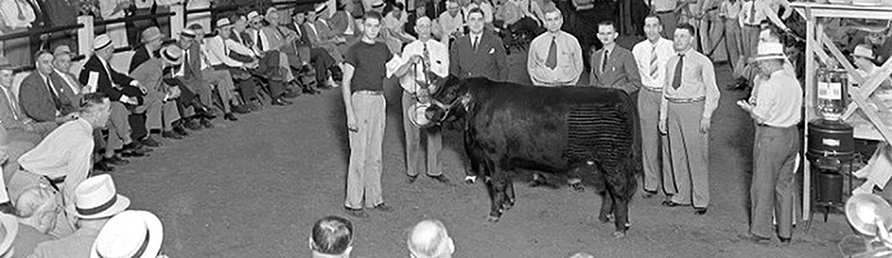

Queen Valentine (Rural Post-Industrial)

Queen Valentine is “found art” that is being recast in the context of the post-industrial rural environment and the art of animal husbandry and livestock exhibition. Those engaged in the breeding and exhibition of livestock such as cattle, sheep, horses, llamas, and other animals that are raised for a commercial value more than companionship have a wide range of interests and intentions for their endeavor. Despite the lack of artistic intent or the intent in the sense of traditional art forms by all practitioners and a dearth of widespread recognition as a form of art; livestock exhibition is an art. It is the art of livestock breeding that also contributes to ecology damage and decrease in biodiversity and habitat. Controlled breeding of cattle that includes sexing semen, embryo transfers and cloning are part of carefully crafting the form, composition, texture, performance and other characteristics of the animal. In 1904, the Hon. W. A. Harris of the American Shorthorn Breeders’ Association gave a presentation for the Missouri Agriculture report. He affirmed that “No man can be a successful breeder of cattle unless he looks at his animals with affection. He must love the beautiful animal which grazes upon the grasses of his farm. He must take pleasure in looking back over the history of his animal. How they have been produced and gradually come to us, and the different stages and people with whom they have been associated.” While not declared an “art” Harris’s reference to the “sentimental side” of the livestock breeder is analogous to “art” in the professional and academic sense. Despite the negative environmental aspects of the art of livestock exhibition and animal husbandry, there is a key cultural opportunity to re-imagine the rural as a place ripe for creative exploration. Post-industrial has transformed animal breeding into an abstraction that is largely removed from any need or commercial value even in strictly agri-business terms let alone as it concerns the overall health of the rural environment. There is a compelling need to understand livestock exhibition and animal husbandry in terms of both ecology and art.

Queen Valentine is “found art” that is being recast in the context of the post-industrial rural environment and the art of animal husbandry and livestock exhibition. Those engaged in the breeding and exhibition of livestock such as cattle, sheep, horses, llamas, and other animals that are raised for a commercial value more than companionship have a wide range of interests and intentions for their endeavor. Despite the lack of artistic intent or the intent in the sense of traditional art forms by all practitioners and a dearth of widespread recognition as a form of art; livestock exhibition is an art. It is the art of livestock breeding that also contributes to ecology damage and decrease in biodiversity and habitat. Controlled breeding of cattle that includes sexing semen, embryo transfers and cloning are part of carefully crafting the form, composition, texture, performance and other characteristics of the animal. In 1904, the Hon. W. A. Harris of the American Shorthorn Breeders’ Association gave a presentation for the Missouri Agriculture report. He affirmed that “No man can be a successful breeder of cattle unless he looks at his animals with affection. He must love the beautiful animal which grazes upon the grasses of his farm. He must take pleasure in looking back over the history of his animal. How they have been produced and gradually come to us, and the different stages and people with whom they have been associated.” While not declared an “art” Harris’s reference to the “sentimental side” of the livestock breeder is analogous to “art” in the professional and academic sense. Despite the negative environmental aspects of the art of livestock exhibition and animal husbandry, there is a key cultural opportunity to re-imagine the rural as a place ripe for creative exploration. Post-industrial has transformed animal breeding into an abstraction that is largely removed from any need or commercial value even in strictly agri-business terms let alone as it concerns the overall health of the rural environment. There is a compelling need to understand livestock exhibition and animal husbandry in terms of both ecology and art.

Stonehead Nature Preserve - IN

Images taken at small wetland preserve in Brown County, IN.

CentralIA - 02/19 - Passage 01