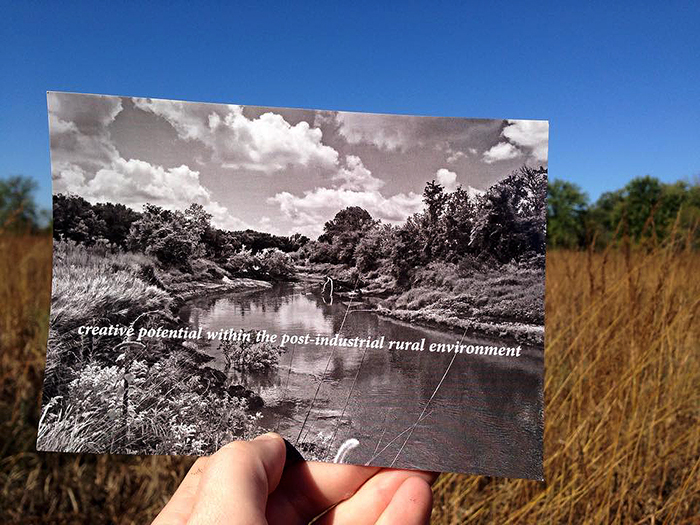

Creative Potential in the Post-Industrial Rural Environment

Vision

Inquiry is the creation of knowledge or understanding; it is the reaching out of a human being beyond himself to a perception of what he may be or could be, or what the world could be or ought to be.

C, West Churchman - The Design of Inquiring Systems

The site for this inquiry is the landscape of the Midwest, which was defined by tallgrass prairie before its radical transformation by European settlers into a leading agricultural center during the middle of the 1800s. Industrialization fostered production efficiency through scale and new technologies, reducing human labor and increasing output. In our current situation few people are needed to farm the land and farms are becoming fewer and larger. The notion of “peak farmland,” a time when land can be removed from agricultural production is no longer tenable because it was based on industrial farming methods that are unsustainable. Hence, the very notion of a “post-industrial” rural condition may seem to be mired in contradictions. We use the term to acknowledge the significance of

pre-industrial knowledge and practices and the values of cultural and material vibrancy and biodiversity. The post-industrial condition is defined by interdependencies, not the isolation of elements within discrete parts which is the model characteristic of industrial practices. The functional grids and boundaries overlaid across the Midwest invoke a sense of predictable regularity and aesthetics of human dominance over nature through “improvement” of the land. The establishment, transgression and transformation of boundaries on the land itself, between nature and culture, human and nonhuman and the role of human engagement, management and control of the environment are the dominant themes that emerged during our exploration of the post-industrial rural landscape. While terms such as conservation and restoration may imply we have the ability to undo the effects of industrial agriculture; in reality, it is a boundary we can no longer transgress. An exploration of the tension between control and that which escapes or eludes our control suggests how we may reconnect to hidden or lost dimensions of the post-industrial rural environment.

- K. Lair, Co-director WAS, 2014

Inquiry is the creation of knowledge or understanding; it is the reaching out of a human being beyond himself to a perception of what he may be or could be, or what the world could be or ought to be.

C, West Churchman - The Design of Inquiring Systems

The site for this inquiry is the landscape of the Midwest, which was defined by tallgrass prairie before its radical transformation by European settlers into a leading agricultural center during the middle of the 1800s. Industrialization fostered production efficiency through scale and new technologies, reducing human labor and increasing output. In our current situation few people are needed to farm the land and farms are becoming fewer and larger. The notion of “peak farmland,” a time when land can be removed from agricultural production is no longer tenable because it was based on industrial farming methods that are unsustainable. Hence, the very notion of a “post-industrial” rural condition may seem to be mired in contradictions. We use the term to acknowledge the significance of

pre-industrial knowledge and practices and the values of cultural and material vibrancy and biodiversity. The post-industrial condition is defined by interdependencies, not the isolation of elements within discrete parts which is the model characteristic of industrial practices. The functional grids and boundaries overlaid across the Midwest invoke a sense of predictable regularity and aesthetics of human dominance over nature through “improvement” of the land. The establishment, transgression and transformation of boundaries on the land itself, between nature and culture, human and nonhuman and the role of human engagement, management and control of the environment are the dominant themes that emerged during our exploration of the post-industrial rural landscape. While terms such as conservation and restoration may imply we have the ability to undo the effects of industrial agriculture; in reality, it is a boundary we can no longer transgress. An exploration of the tension between control and that which escapes or eludes our control suggests how we may reconnect to hidden or lost dimensions of the post-industrial rural environment.

- K. Lair, Co-director WAS, 2014

WAS Co-director Elizabeth Walden and Momo cutting through the forest.

11/17 - Artist Rebecca Beachy on her Stout Fellowship visit to WAS takes a turn at cutting timber