TELESCOPE - INSTINCT GALLERY

The craftsperson working with metal discovered the structural properties of metal (polycrystalline) in an effort to discover what metal can do, rather than the scientists trying to discover what metal is. The craftsperson discovered the “life in metal” that enabled him to work more productively with it.

- Jane Bennett

Perspectives from science and art can challenge and enhance each other. From an artistic perspective we tend to abstract what is in a resource that can be reformed into the line, color, tone, pattern and other aspects of an aesthetic composition. Science is one of the ways to challenge this practice of art making and attune our gaze towards a deeper understanding of our environment. Science refocuses our view onto the material subject and appreciates aspects that may not seem to lend themselves to formal expression or individualistic statement. The subjects we work with remain part of the environment rather than serve simply as raw material.

Conversely, artistic methods and sensibilities challenge scientific endeavors. Art can challenge the subject being studied so that it is not seen merely as a scientific resource or material. In particular, the perspective of the particular and individual uniqueness is explored. However, both art and scientific inquiries seek patterns and points of divergence or anomaly from the known or expected patterns. A careful study is often necessary to reveal a better understanding and how a pattern is created, shaped and ended. These inquiries mutually reinforce the intrinsic value of materials, assemblies and environments by questioning disciplinary biases inherent in each way of understanding our world. This often becomes a position around advocacy and activism in which disciplines can merge.

I wanted to start looking at things more clearly, and in doing so, I really began to get interested in the soil, in the earth, in everything connected with them that was already going on around me. And I discovered that there was something passionate about it.

- Gianfranco Baruchello

My work in the exhibition Telescope at the Instinct Gallery is part of an on-going creative inquiry into native ecology in the post-industrial rural environment. I have drawn on both scientific and artistic knowledge and methods in my inquiry. Although, I have spent a great deal of time outdoors dealing with ecology first-hand, I was also a bit dispassionate until investing in the transformation that has occurred since settlement. Native ecology and our environmental history in the Midwest (and other places) are characterized by our interest in transforming the native conditions through human labor into something profitable. Settlement by Europeans was characterized by “improving” the land and extracting wealth from its resources. Scientific endeavors have been focused on finding new and more profitable ways to extract more from the environment and produce greater agricultural yields with less labor. My creative inquiry has led to a deeper investigation into these perspectives and current efforts to practice shift scientific efforts for better environmental outcomes.

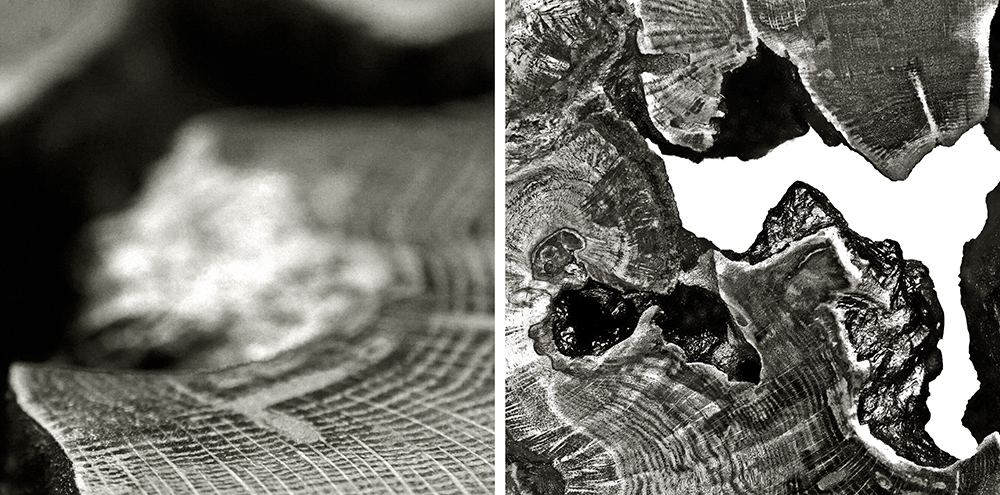

One of the subjects I have focused on is the Oak savanna as a key part of the native ecology. The work represents the complex layers of information that is part of the Oak tree (primarily, the Bur Oak or Quercus macrocarpa) and the rhizosphere it inhabits. The tree embeds local information as well as regional or global patterns. Localized factors such as competition from other plants around the tree may influence growth as well as indications of changes on a much larger scale that shapes a tree’s development. Tree growth data is one of the tools used in accessing climate change patterns and is referred to as dendroclimatology. This has led to some controversy as the data in some parts of the world did not verify expected trends and is known as the “divergence problem.” The study of trees as part of a series of systems is inherent in the aesthetic value of the information captured within the tree patterns and forms.

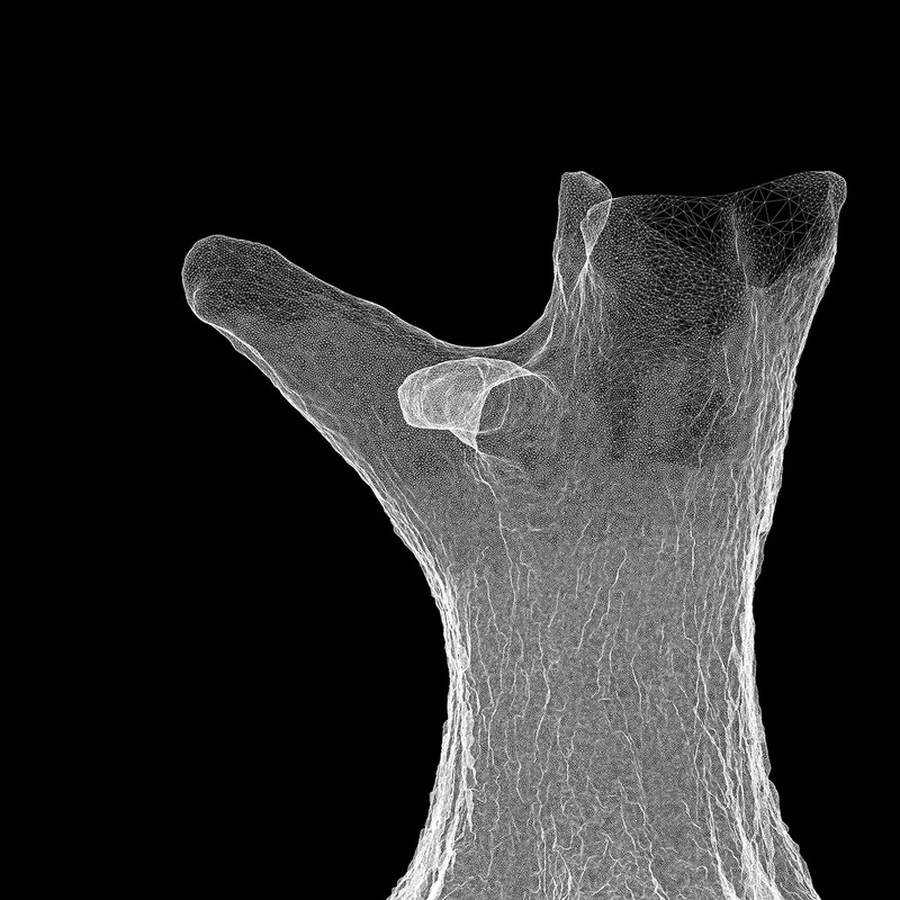

Some of my work in Telescope has utilized software that allows highly detailed three dimensional models to be created of parts of the trees. Images developed from the digital model show the underlying geometry from both inside and outside the tree. Technology has helped foster some of the citizen science through crowd sourcing observation, tracking, mapping and collecting of information. It is also another avenue for advocacy and activism to promote the best scientific inquiry. As noted by Jane Bennett, the craftsperson, the artists, and other non-scientists have advanced our understanding and working knowledge. This may not always be readily apparent or the intent at the time; however, by appreciating the potential of our work such contributions and discoveries are more likely to be realized.

- Jane Bennett

Perspectives from science and art can challenge and enhance each other. From an artistic perspective we tend to abstract what is in a resource that can be reformed into the line, color, tone, pattern and other aspects of an aesthetic composition. Science is one of the ways to challenge this practice of art making and attune our gaze towards a deeper understanding of our environment. Science refocuses our view onto the material subject and appreciates aspects that may not seem to lend themselves to formal expression or individualistic statement. The subjects we work with remain part of the environment rather than serve simply as raw material.

Conversely, artistic methods and sensibilities challenge scientific endeavors. Art can challenge the subject being studied so that it is not seen merely as a scientific resource or material. In particular, the perspective of the particular and individual uniqueness is explored. However, both art and scientific inquiries seek patterns and points of divergence or anomaly from the known or expected patterns. A careful study is often necessary to reveal a better understanding and how a pattern is created, shaped and ended. These inquiries mutually reinforce the intrinsic value of materials, assemblies and environments by questioning disciplinary biases inherent in each way of understanding our world. This often becomes a position around advocacy and activism in which disciplines can merge.

I wanted to start looking at things more clearly, and in doing so, I really began to get interested in the soil, in the earth, in everything connected with them that was already going on around me. And I discovered that there was something passionate about it.

- Gianfranco Baruchello

My work in the exhibition Telescope at the Instinct Gallery is part of an on-going creative inquiry into native ecology in the post-industrial rural environment. I have drawn on both scientific and artistic knowledge and methods in my inquiry. Although, I have spent a great deal of time outdoors dealing with ecology first-hand, I was also a bit dispassionate until investing in the transformation that has occurred since settlement. Native ecology and our environmental history in the Midwest (and other places) are characterized by our interest in transforming the native conditions through human labor into something profitable. Settlement by Europeans was characterized by “improving” the land and extracting wealth from its resources. Scientific endeavors have been focused on finding new and more profitable ways to extract more from the environment and produce greater agricultural yields with less labor. My creative inquiry has led to a deeper investigation into these perspectives and current efforts to practice shift scientific efforts for better environmental outcomes.

One of the subjects I have focused on is the Oak savanna as a key part of the native ecology. The work represents the complex layers of information that is part of the Oak tree (primarily, the Bur Oak or Quercus macrocarpa) and the rhizosphere it inhabits. The tree embeds local information as well as regional or global patterns. Localized factors such as competition from other plants around the tree may influence growth as well as indications of changes on a much larger scale that shapes a tree’s development. Tree growth data is one of the tools used in accessing climate change patterns and is referred to as dendroclimatology. This has led to some controversy as the data in some parts of the world did not verify expected trends and is known as the “divergence problem.” The study of trees as part of a series of systems is inherent in the aesthetic value of the information captured within the tree patterns and forms.

Some of my work in Telescope has utilized software that allows highly detailed three dimensional models to be created of parts of the trees. Images developed from the digital model show the underlying geometry from both inside and outside the tree. Technology has helped foster some of the citizen science through crowd sourcing observation, tracking, mapping and collecting of information. It is also another avenue for advocacy and activism to promote the best scientific inquiry. As noted by Jane Bennett, the craftsperson, the artists, and other non-scientists have advanced our understanding and working knowledge. This may not always be readily apparent or the intent at the time; however, by appreciating the potential of our work such contributions and discoveries are more likely to be realized.

The paired images above are from a Bur oak at WAS. It is a branch that fell during a high wind event from a mature tree. The branch itself is 120 years old. The life of the oak tree requires things to eat it in order to grow. However, there is also consumption that degrades the integrity of the tree.

A detailed 3d digital model created from one of the main Bur oaks at WAS.